If we are to preserve the ocean’s riches for future generations, the problem of marine debris must be resolved. Nets and other fishing equipment make up a significant proportion of sea trash. Now, a startup based in a northern Japan fishing port has launched an initiative to buy old and unusable nets from fishing crews and upcycle them into nylon fibers. What does this company aim to accomplish as its efforts expand beyond its hometown?

It is estimated that more than 11 million metric tons of plastic become marine debris every year, and that roughly 10% of this plastic is abandoned or discarded fishing equipment. Fishing nets set adrift in the ocean, known as “ghost nets,” are a hazard to marine life and a significant concern for society.

One company has begun addressing the fishing net problem directly. Based in the busy regional fishing port of Kesennuma, Miyagi Prefecture, amu inc. buys old nets that are no longer usable and recycles them into nylon fiber or pellets that serve as raw material for making fabrics or apparel products.

KATO Kodai, amu’s founder and CEO, first visited Kesennuma in 2015, when he was still in university. He was one of many young people from around the country who gathered in the port city to contribute toward its recovery from the devastation caused by the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011. While in Kesennuma, Kato vowed to himself that he would one day start a business there to help stimulate its economy. Four years later, he moved there, determined to make good on his vow.

While exploring ideas for business, Kato happened to make the acquaintance of some local longliners, professional anglers who roam the world’s seas in search of tuna. Longline fishing involves casting a single line with multiple branches, each with its own hook, and waiting for the fish to bite. Sometimes longliner crews pursue their quarry around the southern tip of Africa and into the Atlantic Ocean, following shadows in the water below.

Kato was fascinated by the stories these crews told about the global adventures they embarked on from their base in a northeastern Japanese port. But he was shocked to learn that their fishing tools and nets—their very souls, so to speak—could only be used for a few years before they were processed as industrial waste, with no reuse at all.

Certain that there must be a way to reuse rather than simply discard the fishing nets that meant so much to these crews, Kato founded amu in 2023. But getting the business properly on course was far from smooth sailing.

Thanks to his existing contacts, Kato had no difficulty gaining the trust of the local fishing industry and developing a system for collecting discarded fishing equipment. But then came the next challenge: sorting.

Fishing nets are mostly nylon, but some have iron or other plastic parts, and these had to be removed. There are also many varieties of nylon, each one suited to different fishing techniques and types of fish. These varieties differ in their chemical composition, and so amu had to reach out to one of its investors—a major corporation that handles nylon materials—to request their help with analysis. But as issues arose, amu solved them one by one.

Once the nylon is sorted, amu recycles it in one of two ways: “material recycling,” a physical process that involves crushing, cleaning, melting and reforming, and “chemical recycling,” which improves purity by dissolving the nylon chemically and returning it to its raw ingredients.

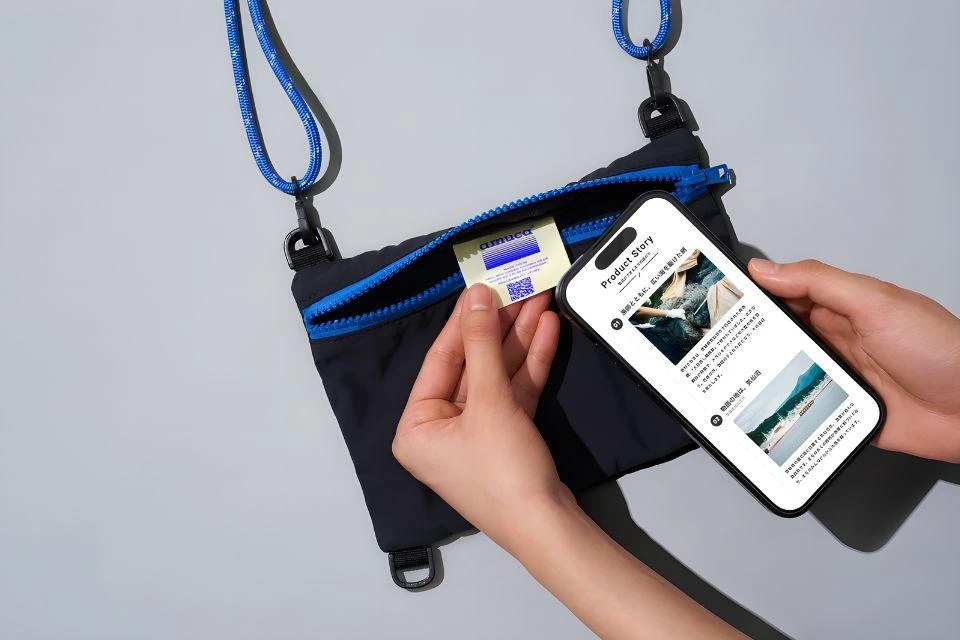

The result of these recycling processes is a material that amu calls “amuca.” Today, amuca is available in pellet, fiber, and textile form, and amu also collaborates with other companies to produce T-shirts, tote bags, and sacoches.

Each product made from amuca has an “amuca tag” with a matrix barcode. Scanning this barcode with a phone reveals more information about how the amuca was made, including where the fishing nets were recovered, who provided them, and how they were recycled. This lets consumers learn the entire story of the transformation from fishing nets to products.

“Fishing nets are used with care and repeatedly mended; they’re a fisher’s soul,” says Kato. “Reducing marine debris is important, of course, but I am also determined to bring this region’s story to people who live in urban areas—to share its history and culture, which is intertwined with the sea, by sending discarded fishing equipment back into the world as fibers, fabrics, and products.”

As of December 2025, amu had recovered 100 tons of fishing equipment at more than 50 recovery centers, from Hokkaido in Japan’s north to Okinawa in the south. By 2028, the company aims to collect 1,000 tons of equipment annually from all over Japan. If this business model spreads worldwide, it could help reduce the amount of plastic adrift in the ocean.

The company name “amu” is a Japanese word meaning “weave.” The name is indicative of Kato’s desire to take things that society deems valueless and weave them into something of value through new ideas and processes. In another sense, his initiative is also a way to weave together the stories of fishing ports throughout Japan.