Winter in Japan’s Kansai region means still, snowy landscapes side by side with warm, bustling human activity. Breathtaking scenery, deep-rooted traditions, seasonal flavors: here we introduce some of the essential experiences that make winter in Japan—and Kansai in particular—an irresistible tapestry woven from the worlds of people and nature.

“Bridge to the Heavens”: A Gateway to Another World

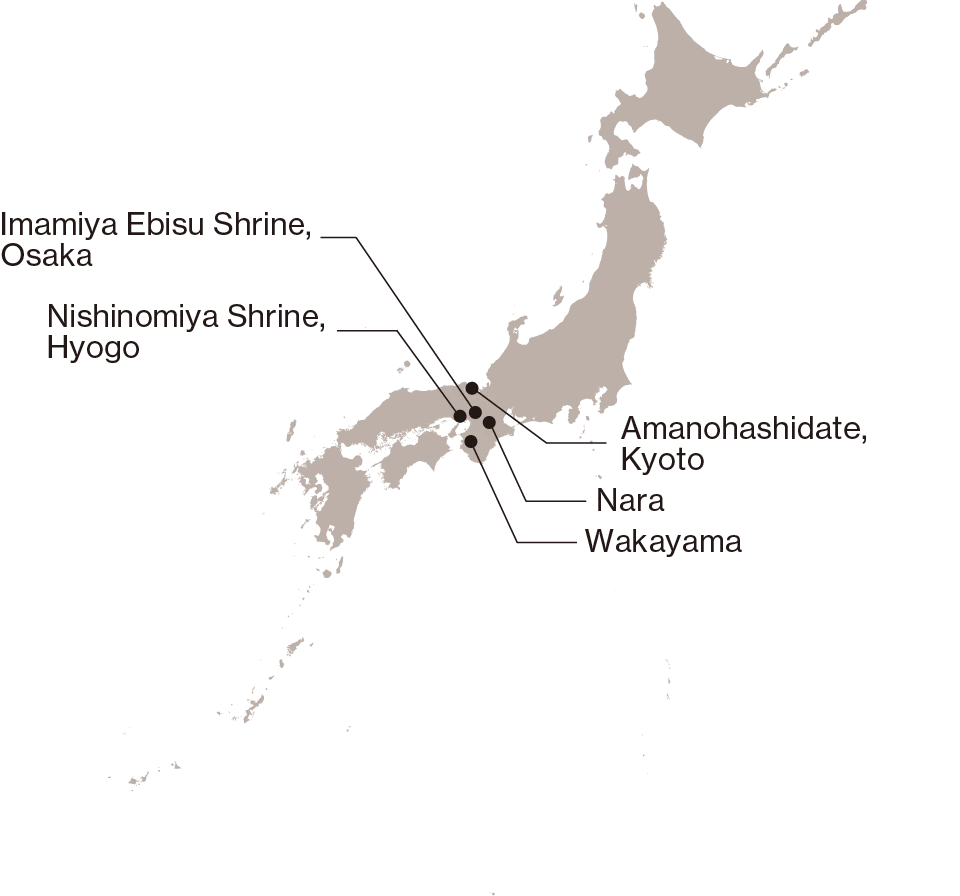

Amanohashidate is a long, narrow sandbar extending some 3.6 kilometers across Miyazu Bay in northern Kyoto Prefecture. Created by natural processes over thousands of years, it ranges from 20 to 170 meters in breadth and is densely covered with some 6,700 pine trees. The mysterious beauty of this rare formation has earned it a place alongside Matsushima in Miyagi Prefecture and Miyajima in Hiroshima Prefecture as one of Japan’s renowned “Three Great Views,” a trio of scenic sites celebrated since the seventeenth century. The name Amanohashidate, which means “Bridge to the Heavens,” first appears in the Tango Fudoki, a gazetteer about the province of Tango (present-day northern Kyoto) compiled in the year 713. Like a celestial bridge over the water, the sandbar was believed to be traversed by the divine beings known as kami. In winter, when the pines are covered with snow, the scene looks like a classical ink wash painting. The views from nearby observation decks of the sandbar stretching across the bay, the villages on the opposite shore, and the mountains rising beyond are almost otherworldly in their beauty.

A Winter Festival to Pray for Prosperity

Toka Ebisu is a festival held every year from January 9 to 11, chiefly in western Japan, in honor of Ebisu, the kami of prosperity. At Osaka’s Imamiya Ebisu Shrine, the lanterns glow warmly all night during the festival, illuminating a compound filled with worshipers eager to receive fukuzasa, bunches of bamboo grass adorned with auspicious symbols. These are distributed by fukumusume, or “girls of good fortune,” traditional mediators of the relationship between worshipers and Ebisu. Their lively cries of “Shobai hanjo de sasa motte koi!” (literally “Bring some bamboo grass and your business will prosper!”) are an iconic part of the festival. Having received their fukuzasa, worshipers make cheerful prayers for another good year.

At Nishinomiya Shrine in Hyogo Prefecture, Toka Ebisu is highlighted by an early-morning ceremony on January 10. When the gates are thrown open at 6 a.m., crowds of worshipers race the 230 meters to the main shrine building, where the first three to arrive are hailed as fukuotoko, or “men of good fortune” (a traditional term; people of any gender are welcome to participate), harbingers of good times ahead in the coming year.

Toka Ebisu is a bustling winter event and an example of how traditional beliefs still thrive in Japan amid contemporary urban culture.

Photo by Mainichi Newspaper/AFLO

Terraced Fields Gleaming Orange in the Winter Sun

Wakayama Prefecture produces around one-fifth of Japan’s mikan (the mandarin orange Citrus unshiu), making it the country’s leading source of the fruit. Arida Mikan, cultivated in the prefecture’s central Arida region for more than 450 years, are one of the country’s best-known mikan brands. In 2025, “The Stone Terraced Mikan Orchard System of Arida-Shimotsu Region” was officially recognized as a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. In the wintry cold, the mountainside practically glows with orange fruit catching the gentle winter light. At harvest time, mikan are handpicked one by one and sent out across the country as a beloved winter treat with the perfect balance of tart and sweet flavors. The mikan orchards of Wakayama are more than just agricultural landscapes: they are symbols of the coexistence of humanity and nature that has long characterized the Japanese way of life. These bright, colorful winter vistas warm the hearts of all who see them.

A New Year’s Treat with Two Delightful Flavors

Zoni is a soup enjoyed throughout Japan at New Year’s. Mochi rice dumplings are the standard ingredient, but regional variations abound. In Nara, zoni is usually made with white miso stock for a milder flavor. The dumplings are round, symbolizing wishes for a harmonious (enman, literally “round and full”) year for the family, and the vegetables added are cut into round slices. Nara zoni is also notable for the fact that the mochi in it is eaten after dipping it in a separate plate of sugared kinako (roasted soybean powder). There are few if any other parts of Japan where mochi is removed from the zoni and then flavored differently before eating. In Nara, though, this kind of “flavor change” is part of the zoni experience, making it a unique dish where the varying flavors are part of the fun.