On New Year’s Day 2024, the Noto region of Ishikawa Prefecture was struck by a magnitude 7.6 earthquake. The damage in Noto and surrounding areas was severe, and the region’s centuries-old legacy of traditional crafts took a heavy blow. However, the desire to preserve these traditions as well as help Noto recover from the disaster has inspired a project that is bringing new life to fragments of broken pottery.

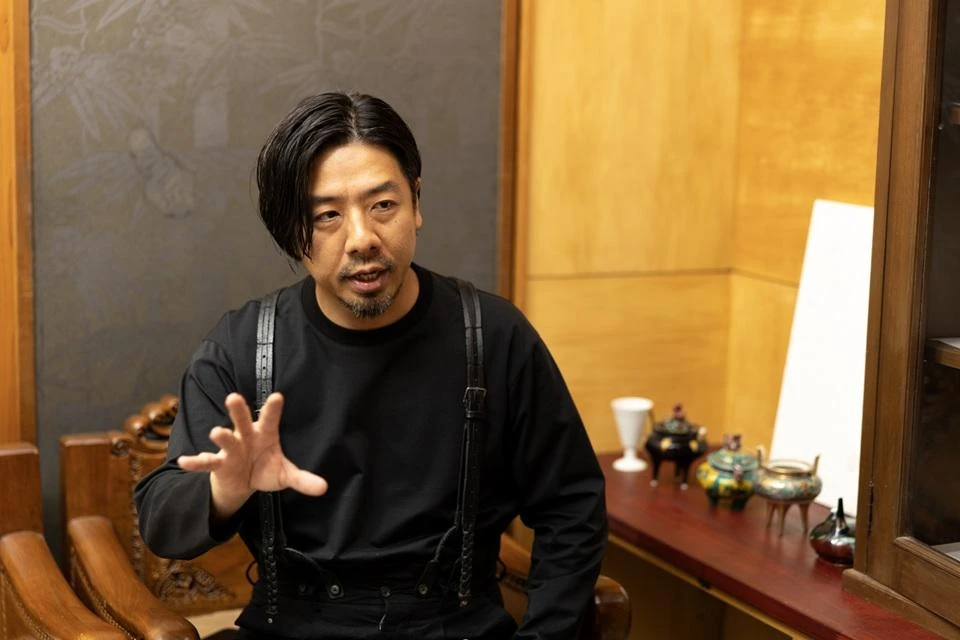

OKUYAMA Junichi, CEO of CACL Inc., breathes new life into pottery that was slated for disposal due to irregularities, along with fragments of pottery damaged in the earthquake.

The Noto region of Ishikawa Prefecture is home to many long-preserved traditional crafts, among them Wajima lacquerware, said to date to the fifteenth century, and Suzu ware pottery, originally produced between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries. But when a massive earthquake struck Noto on January 1, 2024, many of the area’s buildings were damaged or destroyed, with devastating effects on the workshops and products housed there. One company, however, has embarked on a project to reassemble broken ceramic shards and turn them into artworks or products for sale. CACL Inc. is based in the southern Ishikawa city of Nomi, known for its production of Kutani ware, a celebrated porcelain that dates back 370 years.

OKUYAMA Junichi, CEO of CACL, founded the company in 2023 to bring employment support for people with disabilities—a field in which he was already active in the Hokuriku region, which includes Noto—into contact with the world of traditional crafts, where the struggle to secure personnel is so grave that some crafts face extinction. CACL’s initial focus was on facilitating the employment of people with disabilities at certain stages in the Kutani ware production process. As the company’s scope broadened, Okuyama hit on the idea of reusing shards from works rejected before sale due to damage, defects, or marks. That was just before the Noto Peninsula Earthquake struck.

“We immediately set about working with a company that makes and sells Wajima lacquerware, to launch a crowdfunded project called Stand with Noto,” says Okuyama. “CACL also made part of one of its facilities in Nomi available as a temporary workshop for Wajima lacquerware artisans affected by the quake, so that they could continue their work here. The light of traditional craft in this region must not be allowed to go dark. We decided to try doing what we could to prevent that.”

Most of the lacquerware artisans who were invited to work in Nomi have since returned to Wajima, but one, KEIZUKA Hidenobu (pictured), is now a full-time employee of CACL with a permanent workshop there.

CACL also moved to reuse the shards of ceramics shattered in the disaster. The company purchased and collected pieces from workshops in Nomi and kilns in Suzu, ultimately gathering around 10 tons at its Nomi headquarters. Wajima lacquerware artisans then created new vessels from the fragments, joining them together by a technique called kintsugi that uses lacquer painted with gold dust. Other artisans then ornamented the new pieces with maki-e, sprinkling gold dust on additional patterns drawn in lacquer. Because these crafts originally arose in different regions and developed independently, there was no previous exchange between the artisans or their work. Through this project, however, fragments from diverse traditions were combined and reborn as unified craftworks with new value.

New craftworks reborn through the kintsugi technique. Some pieces combine fragments from both Kutani and Suzu ware.

These chopstick rests use fragments of Kutani ware shattered in the earthquake to preserve the memory of the disaster and showcase the beauty of traditional crafts. Each piece is its own world of unique colors and shapes.

Other collaborations to produce works like this involve overseas partners. A joint project with Nigerian artist Otobong Nkanga resulted in a piece exhibited at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, that incorporated Wajima lacquerware, Yamanaka lacquerware, and Suzu ware. GIVENCHY PARFUMS, the French luxury brand known for perfumes and beauty products, engaged artisans to make plates on which to place perfume by combining fragments of Kutani and Suzu ware using Wajima lacquer kintsugi. Projects like this bring fresh ideas and perspectives into the world of traditional crafts.

In Suzu, meanwhile, work has begun on collecting black roof tiles from houses damaged in the earthquake and upcycling them into construction materials. “Rows of black-tiled roofs were an iconic part of Suzu’s traditional streetscape,” says Okuyama. “Even when those tiles break, the orange color revealed in the cross-section contrasts beautifully with the black glaze on the surface. This project began with us asking what use we could find for tiles damaged by the quake.”

CACL gathered black roof tiles from houses in Suzu demolished at public expense and had them crushed by a contractor in Nomi. Under the supervision of an architectural office, the resulting material was reused by a manufacturer of household furnishings and equipment. The idea was to bring the resulting product to the world as a symbol of “creative reconstruction” produced by three companies working hand in hand. The material is expected to see widespread use in building interiors.

“Everything has a positive and negative side,” Okuyama says. “Disasters themselves are tragedies, but there are new cultures that would never have been born if not for those disasters—that’s what I want to believe. A day may come centuries from now when people look back on the quake and say, ‘That disaster was the beginning of a new culture.’”

Okuyama adds: “Depending on how you look at it, even a fragment from a broken vessel can be combined with something else to create a new kind of value. Humans, too, might be imperfect fragments as individuals, but joining with others lets us reach our full potential. I believe that bringing together the traditional cultures of a region affected by disaster can revitalize it. Earthquakes are common in Japan, and people here have a long history of using the wisdom and techniques of their ancestors to overcome the challenges such disasters bring. I plan to continue gathering fragments of all kinds and combining them to produce new value.”

“If regional traditional crafts are to have a future, artisanal techniques must be transmitted, no matter what form that might take,” Okuyama declares. “My hope is that such efforts will aid in the reconstruction of Noto.”