In the Middle East, Africa, and elsewhere, regions with severe water shortages make extensive use of desalination facilities that process seawater into usable freshwater. The Japanese city of Fukuoka, which has no major river nearby, has also adopted desalination technology to solve its frequent water supply issues. But Fukuoka’s desalination plant is very different from other facilities around the world: along with freshwater, it also generates electricity. How did Japanese engineers put two previously unused wastewater streams to work creating renewable energy through osmotic power generation?

The Uminonakamichi Nata Seawater Desalination Center (Mamizupia) has served the Greater Fukuoka metropolitan area since 2005. The plant was built to address the lack of readily available freshwater in Greater Fukuoka, which has 2.6 million residents but no large rivers nearby. Mamizupia can produce around 50,000 cubic meters of freshwater daily—enough to meet the needs of some 250,000 people.

Inside the Mamizupia Seawater Desalination Plant. The facility uses a desalination method in which seawater is pressurized and passed through osmotic membranes to produce pure freshwater.

Even before construction on Mamizupia began, a potential problem was identified: What should be done with the concentrated seawater created as a byproduct of the desalination process?

HIROKAWA Kenji heads Mamizupia for the Facilities Department at the Fukuoka District Waterworks Agency, which manages Greater Fukuoka’s water supply. According to Hirokawa, concentrated seawater, which contains the salt and impurities caught by filters that allow only water molecules to pass, is roughly 8% salt—more than twice the 3.5% salt content of regular seawater. Because discharging concentrated seawater directly into the sea could damage marine ecosystems, Mamizupia initially disposed of it by mixing it with the discharge from a nearby sewage processing plant. Before Mamizupia went into operation, however, researchers were already exploring possibilities for using concentrated seawater instead of simply discarding it. Given global trends toward energy conservation and decarbonization, osmotic power generation was pursued as the best option.

Concentrated seawater is 8% salt.

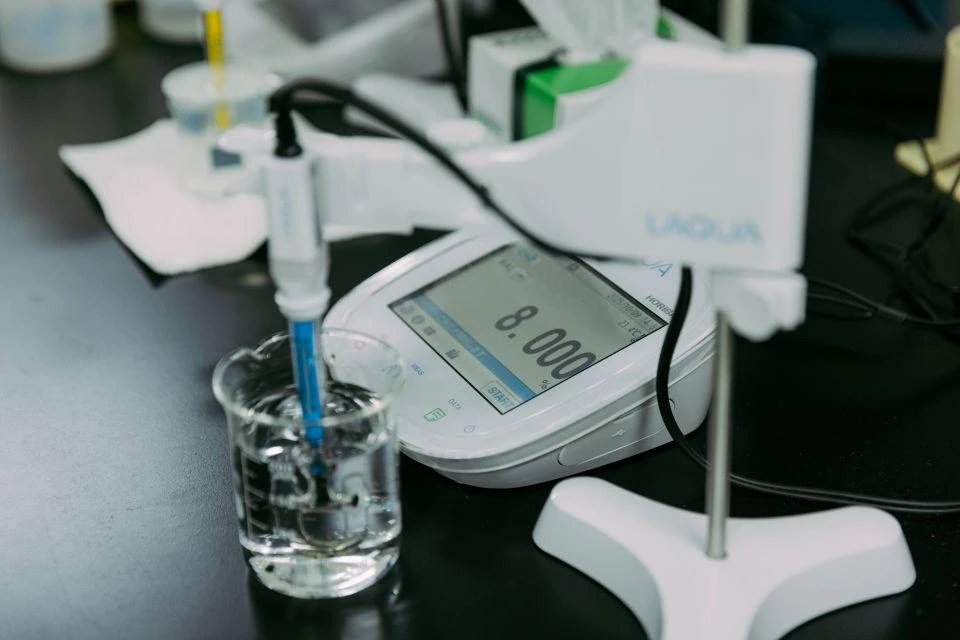

One key player in the osmotic generation project was Kyowakiden Industry Co., Ltd., a water processing plant construction firm that was involved in building Mamizupia. Dr. UEYAMA Tetsuro of Kyowakiden explains the phenomenon of osmosis utilized in osmotic power generation. When two bodies of water with different salt content—like saltwater and freshwater—are separated by a semi-permeable barrier known as an osmotic membrane, water from the side with lower salt content crosses the membrane to the other side, seeking an equilibrium in salt concentration. Osmotic power generation harnesses the kinetic energy of this flow to turn turbines and generate electricity.

Conceptual diagram of the osmotic power generation facility at Mamizupia. The osmotic pressure generated by the difference in salt content between concentrated seawater and treated sewage water is used to generate electricity.

Osmotic power generation at Mamizupia has two main strengths. First, it puts two previously unused wastewater streams, one from the nearby sewage treatment plant, to work generating power. Second, it can generate power 24 hours a day, virtually unaffected by the weather, with extremely high utilization rates of around 90%. Mamizupia is expected to generate around 880,000 kWh per year, which is enough to power 300 average households.

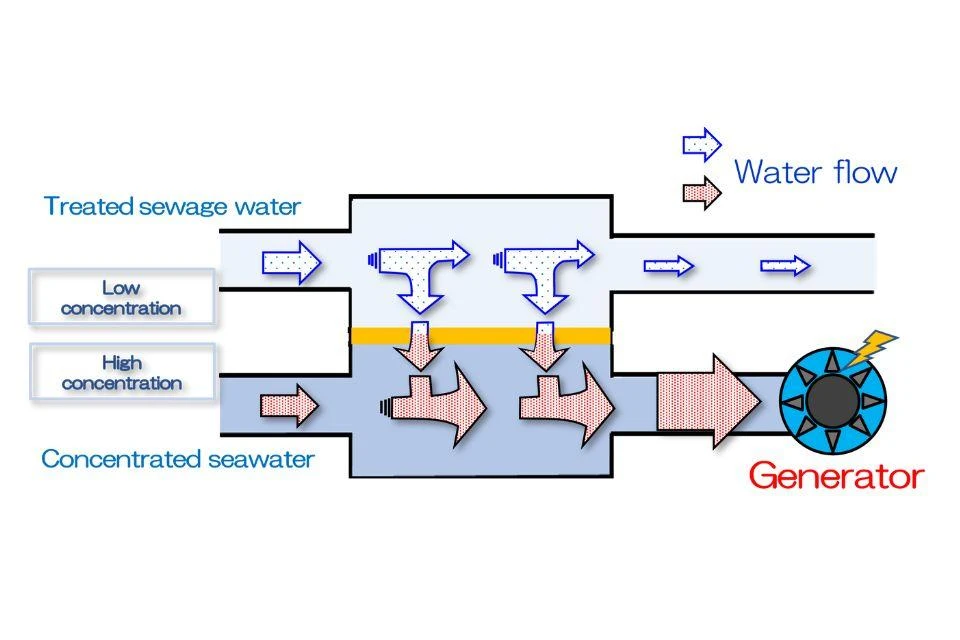

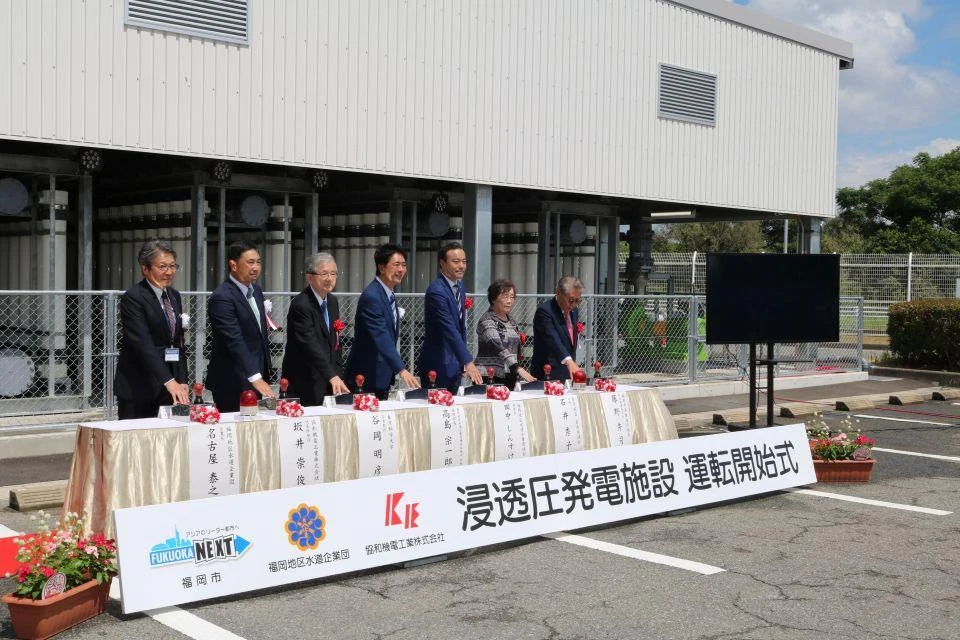

The osmotic power generation facility constructed at Mamizupia. An official opening ceremony was held on August 5, 2025. The red object visible at the rear is the generator; the gray machinery is the turbine.

Given the virtues of the technology, Ueyama is optimistic about its broader possibilities. “A system like this could be deployed in any densely populated region with the necessary infrastructure nearby—a desalination plant, like Mamizupia, and a sewage treatment facility—which gives it high potential for global expansion. Our initial target is the Middle East. Not only does the region have more desalination facilities than anywhere else in the world, but many of those facilities are very large. For example, the United Arab Emirates is home to one of the world’s largest desalination plants, which produces around 909,000 cubic meters of water daily. The utilization rate of osmotic power generation rises in proportion to the facility’s size. So compared to Mamizupia, which generates around 110 kW from 20,000 cubic meters of water per day, we can expect vast amounts of electricity to be produced.”

Hirokawa chimes in again on the ultimate objectives of the project. “Eventually, we hope to achieve osmotic power generation using ordinary, non-concentrated seawater. Since seawater makes up some 97.5% of all water on the planet’s surface, this would be a major contribution to building a sustainable world.”

To achieve this breakthrough, Hirokawa adds, the most urgent necessity is more efficient osmotic membranes. Japan is among the world’s leaders in water treatment technology, with a roughly 60% share of the global market for desalination membranes. The day when a next-generation membrane enables osmotic power generation with regular seawater may not be far away. As a key facility for verifying advances in that field, Mamizupia is sure to attract notice from around the world.

From left: Dr. UEYAMA Tetsuro of Kyowakiden Industry Co., Ltd., and HIROKAWA Kenji, director of Mamizupia for the Fukuoka District Waterworks Agency’s Facilities Department.