2018 is a significant year for Japan, as it marks the 150th anniversary of the Meiji Restoration. The Meiji Restoration was a major revolution that brought an end to over 260 years of feudal government. In its place, a democratic social and political system was established based on constitutional law over the course of about 20 years, and it led to significant economic reforms and growth.

“The driving force behind the Meiji Restoration was a strong desire for freedom,” says Shinichi Kitaoka, President of the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and Professor Emeritus of the University of Tokyo, who specializes in modern Japanese politics and diplomacy.

Shinichi Kitaoka

President of JICA since 2015. Emeritus Professor of the University of Tokyo. His specialty is modern Japanese politics and diplomacy. He has taught at multiple universities and has also served as Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary (Deputy Permanent Representative of Japan to the United Nations) and on various committees established by the Government of Japan.

Having begun with the rise of the feudal Tokugawa Shogunate in 1603, the Edo period saw Japan mature both economically and culturally. At the same time, however, the Edo period was bound by a strict class structure, which even placed restrictions on access to education, meaning that Japanese society was far from free. It was the Meiji Restoration that finally abolished the strict class system and created a more free and democratic system that allowed the Japanese people to unleash their full potential.

Under this new democratic system, Japan modernized and developed rapidly. In order to facilitate this process, the Meiji Government turned to the models set by the U.S. and European countries.

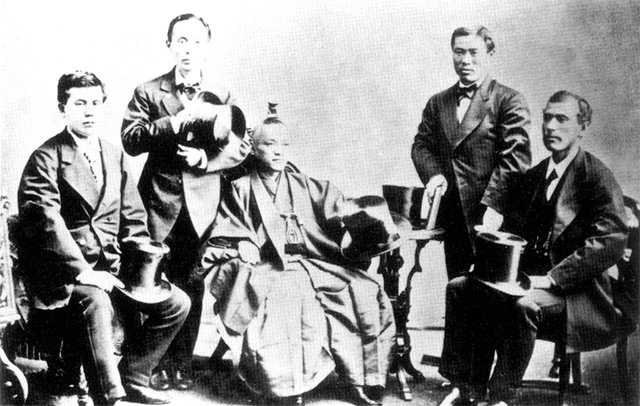

In 1871, Tomomi Iwakura, Udaijin (Minister of the Right) under the Meiji Government, set off from Japan as Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary on a diplomatic expedition known as the “Iwakura Mission.” With 107 top government officials, scholars and young students participating, the Iwakura Mission spent over a year traveling through the U.S. and various countries of Europe. Kitaoka explains, “The Iwakura Mission observed and recorded in great detail various aspects of American and European societies, from politics to industry, commerce and even agriculture. Through their observations, they came to realize that the military power of western nations lies in their industrial might. Not long after the mission, Japan became fully focused on the introduction of policies intended to enrich the nation through modernization and industrialization. Thus, it is no overstatement to say that Japan’s modernization began with the Iwakura Mission.”

Today, 150 years after the Meiji Restoration, that same spirit still lives on in Japan. Under the leadership of Kitaoka, JICA serves as an implementing agency of Japan’s Official Development Assistance (ODA) tasked with promoting international cooperation for developing countries. Kitaoka carries out his tasks “out of a desire to share with other countries Japan’s own experience of successfully modernizing in the years following the Meiji Restoration,” he explains. “As the first non-Western nation to become a developed country, Japan built itself into a country that is free, peaceful, prosperous and democratic while preserving tradition. It is our hope that Japan will serve as one of the best examples for developing countries to follow in their own development. Japan modernized under democratic ideals, with an established legal system and while proactively learning from other countries. I firmly believe that there are quite a few aspects of Japan’s experience that can provide lessons for developing countries today.”

The Iwakura Mission set off from Japan on November 12, 1871 with 107 members, including top government officials, scholars, and others. The mission lasted around one year and ten months, traversing the continental United States and then visiting a range of countries in Europe.

JICA provides active cooperation for primary schooling around the world. The photo shows an elementary school in Ethiopia supported by JICA.

According to Kitaoka, the fact that Japan was able to modernize while still preserving its own traditions makes its experience particularly valuable. “If we force our support upon developing countries while ignoring their culture and traditions, the support will not be able to last for long. Japan pushed forward with modernization, focusing our efforts on such cornerstones of national development as education, public health and infrastructure, while at the same time maintaining our treasured culture and traditions. JICA also strives to give proper consideration to local cultures while offering the types of support that will take root within the context of those cultures.”

In 2018, JICA launched “JICA Program with Universities for Development Studies (JProUD),” a program that invites future leaders from developing countries to Japan to complete master’s degrees at Japanese graduate schools, where they learn about Japan’s experiences with its own modernization and with providing development cooperation to other countries.

Kitaoka has high hopes for this program. “I believe that these students will not only study in their respective academic fields, but will also learn much from modern Japan’s experience of development, which differs significantly from the history of growth and development found in the West. Of course, Japan’s process of modernization also had its share of negative aspects, such as war and serious industrial pollution. I hope that these students will study the ‘Japanese experiences’ systematically, including negative ones, so that they may use this knowledge to contribute to the development of their own countries.”

Reflecting on the 150th anniversary of the Meiji Restoration, Japan hopes to use this opportunity to contribute even more to the development of other countries.