Fibers are utilized by society in diverse ways, from clothing to industrial applications. However, petroleum-based synthetic fibers raise environmental concerns associated with their disposal, including their contribution to microplastic pollution. A natural material developed in Japan not only promises to resolve such issues, but also possesses remarkable strength. The key lies in the bagworm—a tiny creature with heretofore hidden potential.

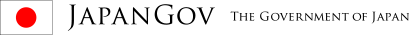

Bagworms being raised at the Kowa Research Laboratories for Advanced Science (left). The labs have created ultra-thin, nonwoven fabric-like MINOLON sheets (right) from the silk threads spun by the bagworms.

Until now, spider silk has laid claim to being the world’s strongest natural fiber. Its strength is four times that of steel, its elasticity rivals that of nylon, and it can withstand temperatures exceeding 300 degrees Celsius. However, spiders have cannibalistic tendencies that make large-scale breeding for commercial applications extremely difficult.

In 2018, the National Agriculture and Food Research Organization (NARO) and Kowa Company, Ltd., a manufacturer of pharmaceuticals and optical equipment that also imports and exports textiles and building materials, announced surprising joint research results.

They discovered that bagworm silk surpassed spider silk in all indicators of durability: approximately 2.3 times greater toughness (flexibility to withstand deformation without breaking) and about 1.8 times higher tensile strength (force that can be withstood before breaking when pulled). This research was published the following year in the international scientific journal Nature Communications.

Holding a bagworm, a moth larva that spins silk of remarkable strength, is ASANUMA Akimune, Ph.D., Executive Officer and Senior Manager, Future Business Development Office, Corporate Strategy Division at Kowa Company, Ltd.

“Bagworm” is a general term for moth larvae of the order Lepidoptera, family Psychidae. Some 1,000 species exist worldwide, about 50 of which are found in Japan. The giant bagworm (Eumeta variegata) is the most well-known species in Japan. Bagworms spin their own silk to bind bits of leaves and twigs to form the nests they wrap themselves in, as well as to hang from branches for protection from predators and to move from place to place.

“Bagworm silk is made of protein, just like silkworm and spider silk. When we analyzed the amino acid sequences that make up the protein, we found that it has a highly ordered hierarchical structure, which is what provides its high strength,” says ASANUMA Akimune, Ph.D., Executive Officer and Senior Manager of the Future Business Development Office, Corporate Strategy Division at Kowa.

To commercialize this revolutionary natural fiber, Kowa established the Kowa Research Laboratories for Advanced Science in Tsukuba City, Ibaraki Prefecture, and began joint research with NARO on the artificial breeding of bagworms. With no bagworm specialists on hand, team members initially spent their days collecting, breeding, and observing bagworm behavior. The first step toward industrial application came with their discovery of a breeding method that leverages the characteristics of the bagworm lifecycle. Whereas silkworms spin silk only for two or three days just before pupation, bagworms begin spinning silk immediately after birth and continue throughout their larval stage. The team then developed indoor breeding methods and established a system for continuous silk collection.

Moreover, bagworms spin zigzag ladder-like silk threads and use them as scaffolding for their movement. Based on this “foothold silk,” Kowa successfully created ultra-thin nonwoven fabric-like sheets at a rate of up to 1,000 square meters annually.

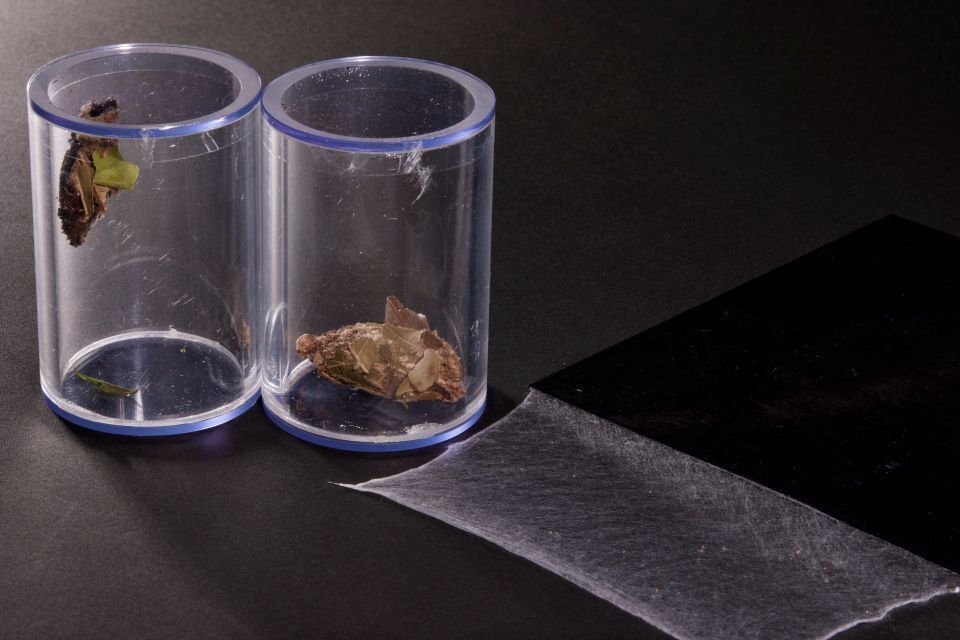

Magnification of MINOLON sheets under a microscope reveals that randomly overlapping bagworm fibers are bonded together, creating a structure capable of distributing applied force over a wide area.

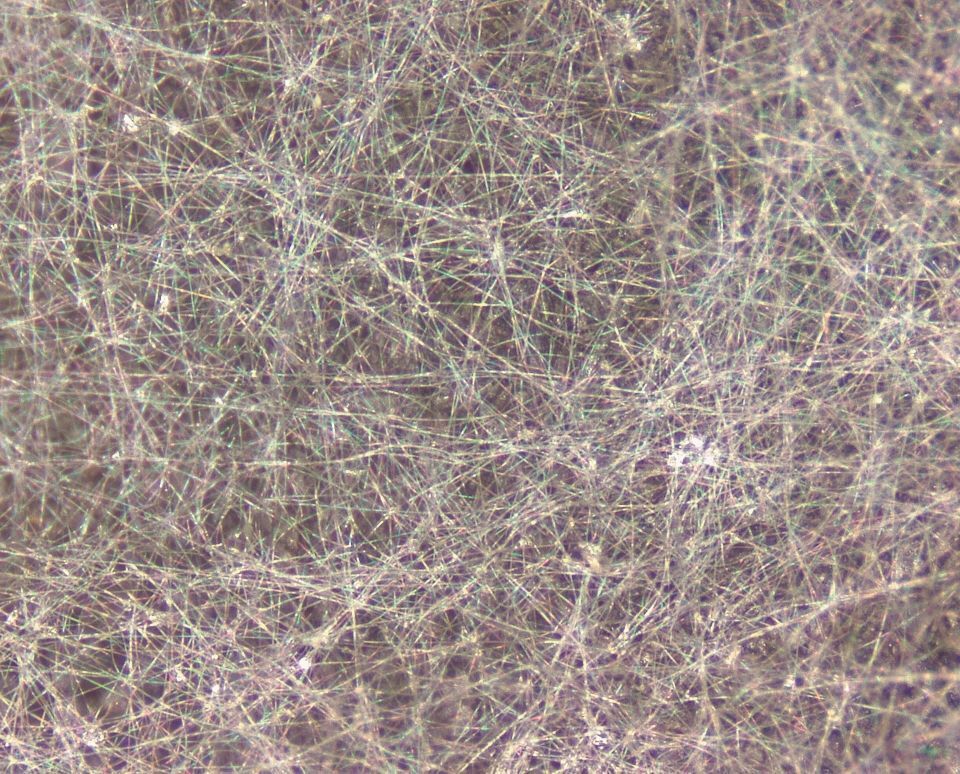

Made of natural amino acids, bagworm fibers decompose in natural environments. These photos show the progress of a fiber disintegration test conducted in a marine environment with fibers before testing (top), after 30 days (middle), and after 62 days (bottom). The fibers completely disintegrated after three months.

In November 2024, Kowa successfully commercialized bagworm silk for the first time with the launch of its brand MINOLON.

The first product to utilize MINOLON was a new series of Ezone tennis rackets by sports equipment manufacturer Yonex Co., Ltd. MINOLON was used in the racket shaft by fusing it with advanced carbon materials. With MINOLON’s combination of strength and flexibility, the racket’s vibration damping performance improved by 5.8% compared to conventional products.

“Bagworm silk is made of protein and is biodegradable. Since it’s not derived from fossil fuels, there’s no risk of it turning into microplastics after disposal or negatively impacting ecosystems. We currently use it in composites with plastic, but if we can eventually produce composites with bioplastics, we should be able to develop products with even lower environmental impact,” says Asanuma about future prospects.

Kowa is pursuing low-volume, high-value-added applications that make use of the special properties of bagworm silk. The company anticipates the development of applications in unexplored fields such as aerospace where the fiber’s strength can be employed to maximum effect. Manufacturing that harnesses the hidden properties of living organisms like the bagworm is now opening up new possibilities for the future of fibers.

Senior Manager Asanuma Akimune (second from left), Lab Manager SHIBASAKI Manabu (second from right), and young researchers stand in front of the Kowa Research Laboratories for Advanced Science.