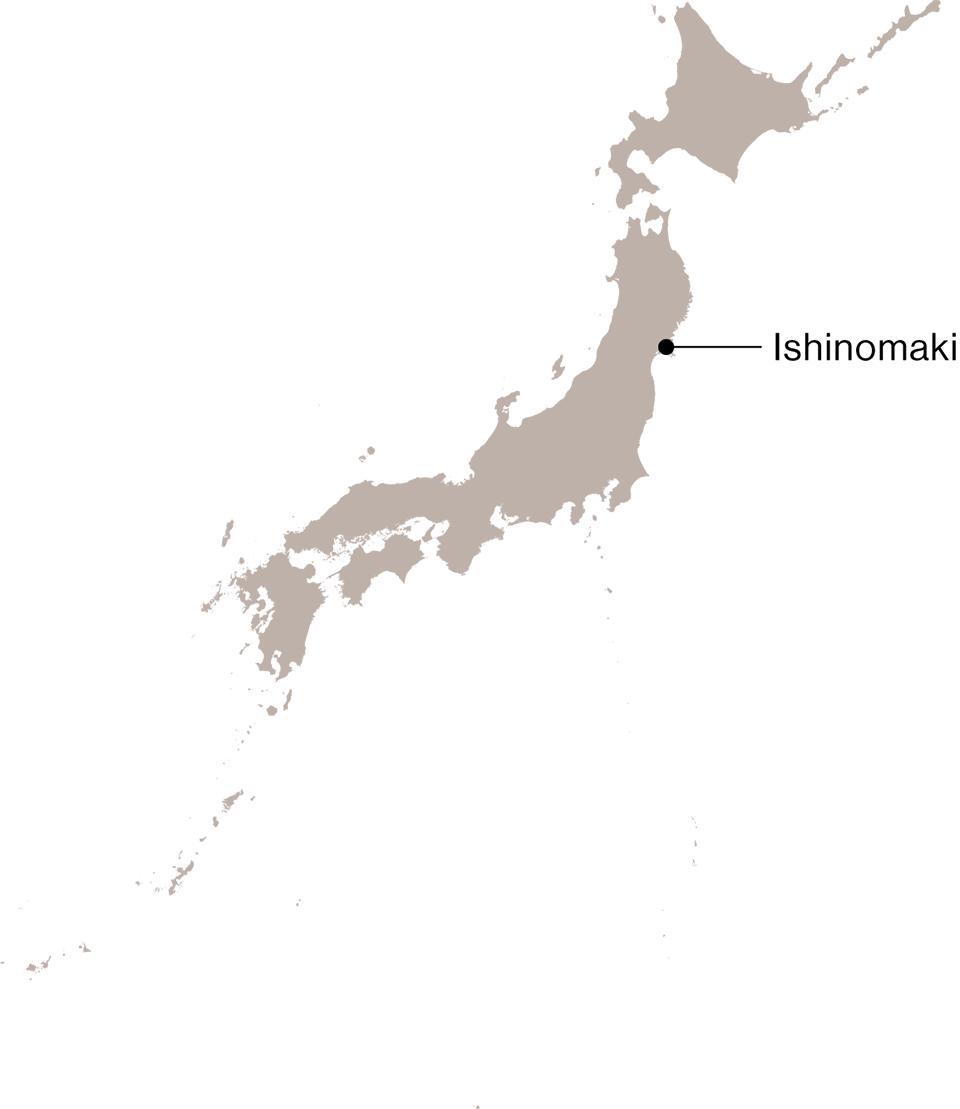

A Ukrainian woman who fled the Russian invasion found herself in Ishinomaki, a city devastated by the giant earthquake of March 2011. Warmly supported by the local people, she speaks about the importance of human life and her desire for peace.

Irina Honcharova stands in front of the ruined building of Kadonowaki Elementary School, which has been preserved as a warning to posterity about the dangers of catastrophic earthquakes. “We will never forget the countries and people who have supported us,” she declares. Her greatest wish at the moment is to return to a peaceful homeland.

Visitors to the former Kadonowaki Elementary School in the town of Ishinomaki in Miyagi Prefecture, part of Japan’s Tohoku region in northern Honshu, are struck by the charred ruins of its three-story building. The site lies less than a kilometer from the sea in an area devastated by the earthquake of March 11, 2011 (the Great East Japan Earthquake), and was engulfed in flames when houses, cars, and other debris were swept around it by a tsunami that carried along a trail of fire. The schoolchildren had fortunately taken refuge on a hill behind the school and were thus all saved.

The damaged building has been preserved and is now open to the public as the Ishinomaki City Kadonowaki Elementary School Ruins, standing as a reminder and a lesson for future generations of the terrible power of tsunamis and tsunami-triggered fires.

Honcharova is a volunteer at the ruins of Kadonowaki Elementary School, where she talks to visitors about her own country. She speaks to them in Ukrainian with the help of an AI interpreter and sings Ukrainian songs when requested.

A regular visitor to the school since September 2022 has been Irina Honcharova, a Ukrainian evacuee who fled the Russian invasion of her homeland last year. She goes there in order to speak to people about the preciousness of human life. Originally she had lived in Chernihiv, a city in northern Ukraine that came under fierce attack by the Russian armed forces, forcing her to shelter in an apartment cellar without water or electricity.

After the Russian siege was lifted, she immediately fled to Poland. Then, when the Japanese government announced that it would accept evacuees, Honcharova came to the country in April of last year along with her then 86-year-old mother. They chose Ishinomaki City because her son lives there with his Japanese wife, and both have helped them to settle in the community.

Three Ukrainians, including Honcharova and her mother, now live in Ishinomaki. The city assists them with living and medical costs and also provides them with a place to live. OSU Mitsuko, who works in the city’s health and welfare department, says that her experiences during the earthquake of 12 years ago have helped her in dealing with the city’s present support of evacuees. “Victims of catastrophe hesitate to express their real concerns. Honcharova was the same way, saying, ‘Oh, I’m fine, I’m fine.’ So rather than repeatedly asking if they have problems, it’s more important for us to be there for them until they can open their hearts and begin to speak up.”

Honcharova says she is grateful for the city’s warmhearted support. “Here, everyone wants to help us. I am especially thankful that someone from the city office is always there to offer support. They found a wheelchair for my mother, and they take her to adult daycare. I cannot thank them enough. At New Year’s, I was so happy to receive many pictures from school children expressing their heartfelt prayers for Ukraine.”

Honcharova is outgoing and eager to socialize with local residents. Here, she is all smiles as she learns to play the koto, a traditional Japanese zither-like instrument, at a neighbor’s home.

Interacting with Honcharova and finding her to be talkative, Osu thought it would be good for her to connect with other people as well. Thus, she suggested that Honcharova volunteer at the Kadonowaki Elementary School ruins. She now goes there twice a month to speak to visitors about Ukrainian culture and society and to voice her desire for peace.

Honcharova taught at an elementary school in her native country for more than a quarter of a century. “For all teachers, school is a kind of home,” she says. “Tears came to my eyes when I first saw the remains of Kadonowaki Elementary School. It made me think of all the destroyed schools in Ukraine. The destruction of a school is like the destruction of a home. It is so devastating,” she sighs.

“Every human being has the right to live,” Honcharova says emphatically. “Military invasions and natural calamities are not the same thing. But the people of Ishinomaki and I share feelings that only those who have suffered can feel.”

March 2023 marks the 12th anniversary of the Great East Japan Earthquake. Ishinomaki, as it continues on its way to reconstruction, stands firmly in support of Ukraine and shares in its desire to cherish human life.

Ishinomaki was among the cities most devastated by the tsunami of March 2011, with nearly 4,000 people either dead or missing. THE GREAT EAST JAPAN EARTHQUAKE ARCHIVE OF MIYAGI

Ishinomaki Minamihama Tsunami Memorial Park is located in a district that suffered extensive damage. The park opened in 2021 to commemorate the victims of the earthquake and tsunami, to pass on the memories and lessons, and to express the city’s firm determination to rebuild, both at home and abroad. ARC IMAGE GALLERY/ AMANAIMAGES