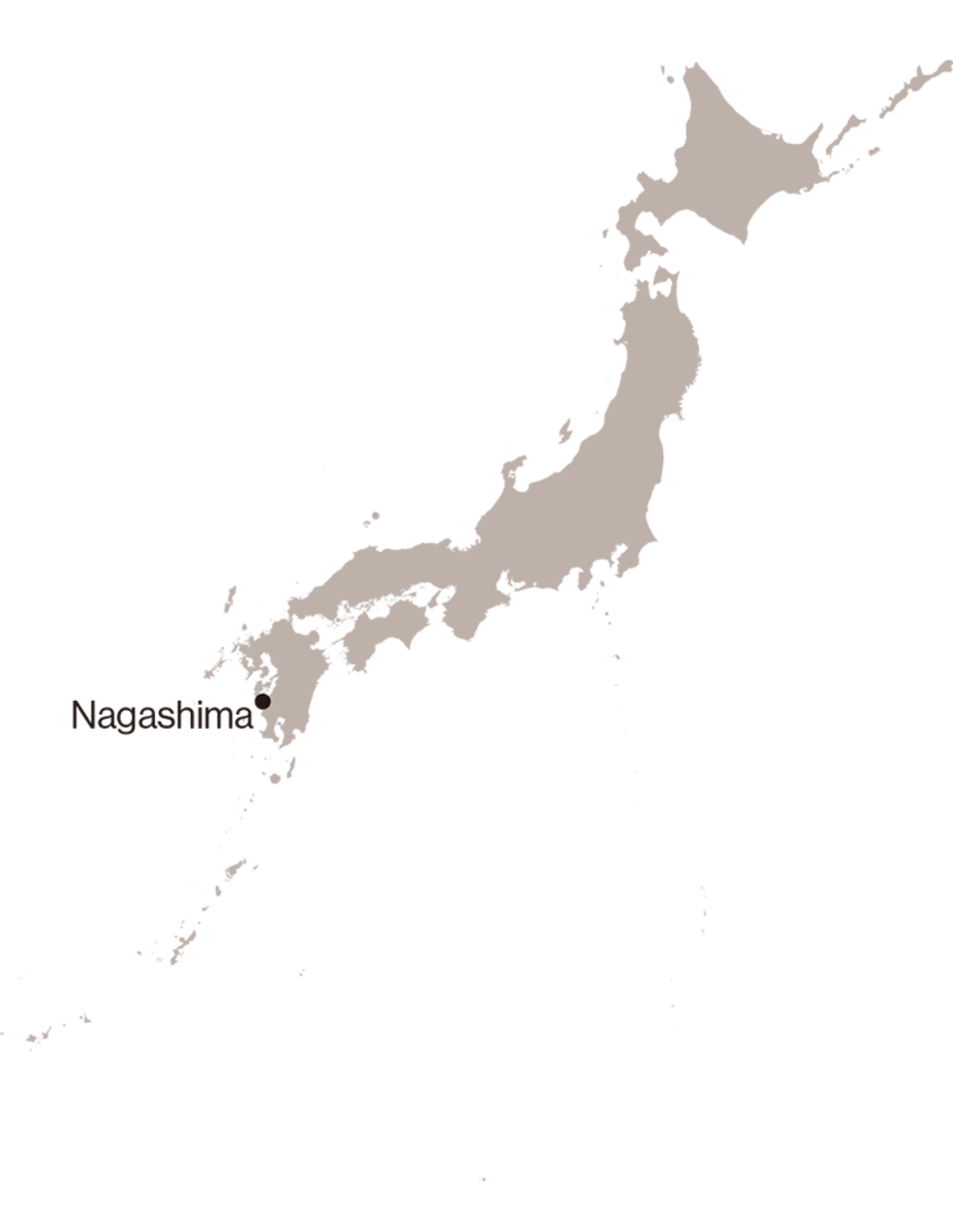

Cultivating Japanese yellowtail to meet the needs of the global market, residents of a vibrant island off the coast of Kyushu have turned fisheries into a growth industry.

Nagashima Town, encompassing a series of fishing grounds stretching across several island bays, is famed for the production system that it developed for exporting fish year-round. The younger generation is actively participating as well: according to a 2018 survey, some 42% of individual owners who own family-run fisheries have successors, a much higher rate than the national average of 17%.

Surrounded by plentiful seas, Japan features a variety of high-quality, local seafood found in each of its regions. While overseas demand for marine products from the country has increased in recent years—driven by the world’s growing appetite for Japanese food—domestic consumption has been shrinking owing to changes in the food culture. Its fishery industry is also faced with an aging workforce and a shortage of successors. Amid those circumstances, Prime Minister Suga’s administration has pledged more support to boost total annual exports for agricultural, forestry, and fisheries products and foods roughly five-fold to 5 trillion yen (45 billion dollars) by the year 2030. Through such strong initiatives, the government aims to give fresh vigor to these primary sectors and turn them into growth industries, leading to the revitalization of local economies.

Nagashima Town in western Kagoshima Prefecture, is one region that has already made great strides. Kagoshima is a major production area for Japanese yellowtail, an endemic fish species in surrounding waters of the country. The fish is known as hamachi in Japanese, and as buri when mature. The town has only 10,000 or fewer residents, yet produces more than 2 million of the fish each year, the biggest output of buri in the whole of Japan. In 2001, it launched the BURI-OH (literally, “king of buri”) brand, and now is responsible for one tenth (over 1000 tons) of the country’s annual export of Japanese yellowtail, boasting sales to as many as 31 countries and territories, mainly in the United States and Europe.

A union of about 120 independent fish farmers, the Azuma-Cho Fisheries Cooperative Association, which handles everything from quality control to shipping, began exports of buri to the United States in 1982. To meet the high food-safety standards required for overseas markets, the association became the first fish farming organization in Japan to acquire Hazard Analysis & Critical Control Points (HACCP) certification, the internationally recognized risk-based system for managing food safety, back in 1998. In order to give the BURI-OH brand its distinctive fleshiness and flavor no matter who has farmed it, the association developed a rigorous production control system to record daily data on fish growth, together with an original, standardized fish feed. It was also essential to design a “market-oriented” approach in order to build a strong brand. Considered a high-end ingredient served in sushi restaurants, buri is enjoyed for its high fat content and full flesh in Western countries. To enable such succulence, fish for overseas market are farmed differently from those for the domestic market: they are raised for a longer time period, and raw fish is added to their feed.

Since its launch, the BURI-OH brand has been enjoyed in Japanese restaurants overseas, mainly as sushi and sashimi.

In Japan, in the face of dwindling sales, small, family-run fishing businesses are increasingly finding it difficult to maintain their operations and to compete with larger companies, but Nagashima Town has successfully overcome such hardships, maintaining independent and family-based operations. This success was possible due to their collective and long-term efforts to develop and improve quality-control techniques and a market-oriented approach, enabling export products that are lucrative on the foreign market. Much of that achievement owes to the leading role played by the Azuma-Cho Fisheries Cooperative Association. However, another important factor in the town’s success is the trust placed in the cooperative, which always puts its farmers and their financial and operational stability first, along with the can-do attitude of the people of Nagashima Town, who are eager to take on the unknown.

While Nagashima Town is blessed by all the optimal conditions for farming fish—warm seawaters and abundant tidal streams—it is also blighted often by damage from red tides caused by algal bloom. When a total of 2.7 million fish succumbed to large red tides in 2009 and 2010, “everyone here thought it was the end of fish farming,” said NAKAZONO Yasuhiko, head of the association’s sales division. But that was followed by a series of innovative measures. Not only did they nurture fish to be shipped out before the summer red tides came, they also successfully created new and productive fishing grounds in waters further offshore, where such problems occur less frequently. Those efforts and the positive results helped to alleviate anxiety among local young people about pursuing careers in the fishing industry, thus paving the way for a new generation of confident successors to Nagashima Town’s fish farms. “We will continue to take on new challenges so that the new generation of farmers can pass on their trade to the next,” says Nakazono.

The approach taken by Nagashima Town, which cherishes the symbiosis between the local environment and its people, while sufficiently addressing industry’s structural problems and carving out a path of economic growth, may be just the model needed to generate greater prosperity in Japan’s local regions.

A farmer nourishes the fish with original, standardized feed. Rigorous production control is carried out in each fish pen with data taken daily on everything from the amount of feed and dosage to the size of the fish.